H. H. Holmes killed at least 27 people and possibly many more before he was hanged in a Philadelphia prison in 1896, according to a story in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Before coming to Philadelphia, Holmes built a hotel in Chicago now known as “The Murder Castle.” It was equipped with secret tunnels and staircases, gas chambers and more devices for torture and death.

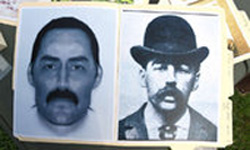

Mark Potts, a history buff from Berks County, Pennsylvania, speculates that Holmes may have also been “Jack the Ripper,” who murdered five prostitutes in London in 1888.

Was Phila. killer Jack the Ripper? on Philly.com.

Pets and recovery from sociopaths

Pets and recovery from sociopaths

Redwald

I can’t resist posting on this topic, having made something of a study of Jack the Ripper in years past.

H. H. Holmes (real name Herman Webster Mudgett) most definitely belongs on the pages of this Web site! Off the top of my head, I’m inclined to say he OUGHT to be America’s most infamous serial killer of all time. The fact that he’s not is worth examining.

It’s not that Holmes is known to have had the highest body count. In the United States (though not in the world), that dubious honor may belong to Gary Ridgway, the Green River killer, who murdered at least 71 women and possibly more. How many victims Holmes was responsible for is unclear, since he himself kept changing his story—naturally he was an inveterate liar along with his other vices—though he finally settled on a count of 27.

Nor was Holmes necessarily the “creepiest” killer. That title should probably be granted to Ed Gein, that ghoul of the 1950s who was indirectly the inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (based on Robert Bloch’s novel).

However, what surely makes Holmes unique in the history of serial killing is the enormous lengths he went to in order to indulge his sadistic vice: the construction of a vast so-called “Murder Castle” with its secret rooms, passages, trapdoors and devices to inflict torture and death on its luckless guests. This all took place under the very noses of his Chicago neighbors, who had no inkling of the horrors taking place inside that building. The sheer scale and complexity of this project alone, and the obsession he must have had to carry it through, makes Holmes stand out from any other serial killer I can think of.

Needless to say, the cold, calculated, instrumental, virtually mechanized way Holmes devoted his energies to his business of killing, for profit as well as perverted pleasure, positively breathes psychopathy from every pore.

The book mentioned in the article, Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City, is an excellent one. I have a copy myself that my wife gave me some years ago when it was first published. Larson interweaves his account of Holmes’s crimes with the story of the 1893 World’s Fair held in Chicago, an absorbing piece of history in its own right. It’s a true tale well told.

Although Holmes made plenty of news back in his own time, what I find curious is that he’s been largely forgotten today despite the remarkable nature of his crimes. Most people have never heard of him, or if they have, they wouldn’t have done so without a revival of interest in recent years, much of it due (I’m sure) to Larson’s book.

Of course, people and events of any kind do tend to be forgotten as they pass into history. People are more likely to remember recent events, particularly those of their own lifetime. Who today is America’s most infamous serial killer in most people’s minds? The name that comes first to my own mind is Ted Bundy, closely followed by John Wayne Gacy, perhaps with Jeffrey Dahmer in third place. Dahmer’s victims were not quite as numerous, but he was notorious for his cannibalism. Bundy was memorable for several reasons, not least that he himself succeeded in turning his trial into a media circus that kept him in the public eye for an extended period of time. I even remember exactly where I was in January of 1989—on a business trip to San Diego, waking up in a hotel opposite Sea World—when I heard the news of Bundy’s execution on the radio, and how a Jacksonville DJ had urged people breakfasting at home that Florida morning to turn off their electrical appliances “to make sure there was plenty of juice for the chair!”

But then, I’m old enough to remember the headlines these particular killers made. I have to wonder if their names are as prominent in the minds of people younger than myself, who may be more likely to think first of serial killers whose capture didn’t make the news quite so long ago. I can’t recall any recently, but some years ago there was Gary Ridgway, and Dennis Rader, who called himself “BTK.” There were those Beltway Snipers too.

Plenty of killers, even serial killers, are little known to the public. As for Faryion Wardrip, say… well, who on earth was Faryion Wardrip? Anyone with a name like that deserves to be obscure!

Despite this tendency to be forgotten as events recede back into time, I am struck by the obscurity into which Holmes has sunk, compared with the enduring fame of Jack the Ripper. They were close contemporaries, yet “Jack,” unlike Holmes, must surely be the most notorious serial killer of all time, the whole world over. There’s almost nobody who hasn’t heard (at least) of Jack the Ripper, even if they’re not familiar with the facts of his crimes. He’s so famous that his nickname has become a sobriquet for many other killers who came after him. These include Peter Kürten the “Düsseldorf Ripper,” Gary Rollings the “Gainesville Ripper,” and Peter Sutcliffe the “Yorkshire Ripper”—not to mention the unnamed “Jack the Stripper” who also killed prostitutes in London in the mid-1960s. Incidentally an amusing story is told of the bungled investigation that left Sutcliffe at large to continue killing for longer than he should have done. At a press conference in the late 1970s, a senior police officer was asked if the Yorkshire force planned to call in Scotland Yard to help them catch the Yorkshire Ripper. He quipped: “Why should we? They haven’t caught theirs yet!”

There’s another sharp contrast between Holmes’s obscurity and the enduring memory of another contemporary of his: Lizzie Borden. All that Lizzie did was to hack her father and stepmother to death with an ax in 1892. It was a savage and sensational killing, to be sure, but a long way from being unique in the annals of crime. Lizzie was acquitted, partly through bias and largely through luck, but everyone knows she did it. She might have been a psychopath too. Does Lizzie owe her lasting fame solely to the mere chance that somebody made up a rhyme about her? “Lizzie Borden took an ax/And gave her mother forty whacks…”

What does make one murderer memorable while others are not? There had to be other factors, especially Lizzie’s being a woman, and from a New England family that was not just respectable but downright “stuffy.” She didn’t belong to the “murdering class,” in many people’s minds; not the ax-murdering class at any rate. Yet a forgotten fact is that until Dr. Harold Shipman outclassed any of his rivals, the British serial killer with the highest body count (in relatively modern times) was, like Lizzie, a woman: Mary Ann Cotton. She probably poisoned as many as twenty-one family members and others close to her between the early 1850s and 1872 when she was caught. The casual way she disposed of anyone who was merely inconvenient to her probably marks Mary Ann as another psychopath. Children chanted a rhyme about her too, though unlike Lizzie’s, it doesn’t seem to have stuck. But poison is said to be a woman’s weapon. An ax is not.

Meanwhile, events of 1910 on that side of the Atlantic ensured that the name of Crippen in England would be synonymous with murder for generations to come. Both Crippen and his wife were American, incidentally, but there were other reasons why that crime stuck in the public memory so long after. Not the least of these was that Crippen had the distinction of being the first murderer to be captured with the help of radio, and a thrilling chase across the Atlantic that riveted public attention in his day the same way that slow-motion car chase did in O. J. Simpson’s.

Whether or not somebody wrote a book about it must also have made a difference to how well the public remembered any particular crime. Today there’s a glut of books about any notable murderer. There are several about Bundy alone. In earlier days this was not the case. But the police officer whose heavy hand fell on Crippen’s shoulder as his ship sailed up the St. Lawrence river toward the safety of Quebec harbor did write his memoirs, which he titled “I Caught Crippen.” In reality Dew’s investigation into Crippen’s wife’s disappearance was no triumph of detection at the outset. If it hadn’t been for an alert ship’s captain equipped with radio, his quarry would likely have disappeared into the tall timber. Dew’s book should probably have been titled “I Nearly Let Crippen Slip Through My Fingers.” But that’s beside the point, and an equally notable fact is that Dew, as a young London constable in 1888, was one of those attending the scene of the Ripper’s last and most gruesome murder, that of Mary Kelly. Naturally Dew didn’t fail to describe that in his memoirs.

Compared with those criminals still infamous today, Holmes’s relative obscurity seems to need explaining. My guess is that in part, his crimes have been overshadowed by those of other multiple murderers: not “serial killers” in the modern sense of the term, but certainly people who killed on a grand scale. America has always been noted for its history of violence, much of it attributable to the lawlessness of the frontier. So the late nineteenth century was still known for outlaws and robber gangs, gunfighters who are still household names today like Billy the Kid, John Wesley Hardin, Jesse James and others. Even after the West had been tamed, violence had taken root in the cities, producing a different crop of household names known for multiple murders, from Baby Face Nelson and Bonnie and Clyde to the most notorious of all, Al Capone—who operated of course close to Holmes’s old stamping grounds in Chicago. With all of that going on in the ensuing decades, perhaps it’s not so surprising that the memory of Holmes and his “Murder Castle” faded into the woodwork.

In contrast, England during the same period was a relatively peaceable nation with comparatively few murders and without the same tradition of gangsterism. No doubt that’s one reason why the horror of Jack the Ripper’s crimes not only shocked London at the time, but continued to be recalled in the generations after. But I’m sure there were additional factors behind Jack’s lasting notoriety, which I’d rather explore in another post when I have time.

For now, I’ll simply add that whether the Ripper should be identified with H. H. Holmes is a proposition I consider highly doubtful—to say the least! Whether that conclusion is right or wrong doesn’t matter though, when historians like Mark Potts are performing a public service simply by drawing attention to these events of the past—utterly free of the type of poisonous “agenda” some other historians can be guilty of. There’s much to be said for innocent inquiry.

Donna Andersen

Redwald – Thank you so much for the waltz through the history of psychopathic killers! Fascinating.