By Eleanor Cowan

By Eleanor Cowan

One winter’s day, busy preparing to drive to a free art lesson for my children and their young friends, my disagreement with my husband took an unwanted turn.

I’d contested Stan’s view of God’s endless compassionate mercy and boundless clemency.

“If that’s so true,” I asked, “What’s hell for?”

My husband was a covert pedophile, although I didn’t know it at the time. Molesting our young daughter and ridiculing our son at every opportunity, while I was at safely at work, Stan never took responsibility for an addiction he knew was morally wrong. Even though he’d molested his own siblings as a teenager, he still felt entitled to become a seminarian as a young man. After that didn’t work out, after we met and married, he felt entitled to molest our children.

Yes indeed, Stan needed to trust in ceaseless forgiveness. God would take care of everything. With no effort on his part other than regular church attendance, he insisted that God solves everything – no need to risk exposing his pedophilia to faulty human personalities who might be judgmental.

Stan liked to remind me of my own history of binge drinking before marriage. Matrimony, he believed, was my salvific solution. I was now back at the church I’d abandoned when I was eighteen and supporting my chronically unemployed husband, a predator content to have me be the sole breadwinner while he excused himself for a decade based on his over-qualifications. Not every unemployed slacker had a doctorate.

“I find your flippancy offensive, Eleanor,” Stan said that day. “I suggest you take a few moments to yourself, perhaps a quarter hour of quiet, so that we can come to some agreement?”

“I’m fine, Stan.” I replied. I’d looked at my own history. I didn’t drink. I’d corrected my past irresponsible behaviors, even though I had a long, long way to go on my journey to self-love.

My son stood close by, all set to leave, when Stan stalled us.

“I’m uncomfortable about our lack of resolution,” he said, “especially your disagreement with me about God’s ceaseless compassion for those struggling with their weaknesses. I find it icy of you.”

My son and I glanced at each other. Dad had the car and the keys to it.

“I suggest you sit for ten minutes, Eleanor, and get quiet with God,” said Stan.

There was no question. I knew what I had to do. A sense of heaviness weighted my body, as I settled in for yet another grueling compromise for the sake of someone or something important. This was the price of getting my kids to the art class. I’d learned previously that if I refused to acquiesce, a valued event, like the art class, a swim or bike ride, would be denied.

I looked at my daughter’s pleading eyes and at my husband’s firm stance.

“Okay, Stan. I’ll be in the living room.”

Like an errant child, I sat on the couch. Taking a deep breath, I sought to quell the squirming, implosive writhing within. Looking out the window to a sunny winter’s day, I heard my son and daughter place their backpacks at the front door. I felt their quiet tension. I knew what I had to do.

“You’re probably right, Stan,” I acquiesced. “God is truly magnificent as you say. Who am I to judge anyone else’s experience with their creator? Thanks for inviting me to think things over.”

“I knew you’d come to your senses, Eleanor. You always do. And just because you don’t drink today, doesn’t mean you’re home free. God’s powerful love shouldn’t be taken lightly.”

Car keys in hand, the kids and I tore off to pick up their friends and arrive at our community center just on time. They all painted happily together. Stan was mollified. I felt lost as I smoked a forbidden cigarette in the parking lot.

Four years of distress later, with the support of a friend and a caring social worker, I made my escape with my children. I fled both my predator and the church that convinced him of its full protection.

I’ll always be grateful to a caring, counselor I visited who explained to me, slowly and carefully, over and over, that family happiness should include me too. While I listened to him politely, I just didn’t get it. It was as though a part of me was asleep or far, far away.

Patiently, he explained to me that at a vulnerable time in my life, after three rapes and the shocking death of my disturbed, alcoholic mother, I may have sought Stan’s protection, but I wasn’t getting it. Instead, I was being exploited by someone who pretended to be superior to me. My counselor said it would never, ever stop.

Somehow, I listened. Somehow, I began to understand how trapped I felt. Somehow, I became willing to escape someone who could only take, and never, ever give.

A day before I left Stan, I visited the counselor again. Once more, he clarified that I was living with a master manipulator.

“Make your move as soon as possible, Eleanor,” he urged me. “I don’t often make such stark recommendations, but I’ve discussed your situation with my supervisor and we both advise you to get out. Run, don’t walk from your hostage-taker. He has problems you will never, ever be able to fix.”

The social worker had some advice for me too. “Eleanor, for the past fourteen years you’ve made it easy for your husband to shirk his responsibilities. You learned a long time ago to tolerate abuse and accept so much less than you deserve. You have some long overdue homework of your own to do.”

Today, thirty years after I’ve left Stan, no one would dare invite me to “get quiet” or withhold car keys from me If I wanted them – for any reason. There’d be no such frightened yielding to manipulation.

An activist and writer, I’m so grateful for the healthy life I’ve earned.

I’m so grateful to have escaped hell.

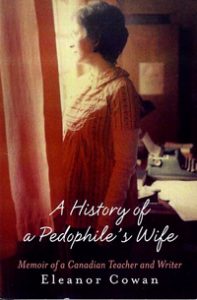

Eleanor Cowan is author of “A History of a Pedophile’s Wife,” which is available on Amazon.com. Visit her at eleanorcowan.ca

regretfullymine

i well remember going to family get-togethers, with him, (his or mine)..watching, listening to him be a ‘nice guy’ laughing, sharing stories, eating food, hobb-nobbing with any and all family/friends. And then..on the way home, being criticized, put down, sometimes yelled at, blamed for any sins, crimes, mistakes misspoken, etc, ect.. when I went to these things alone (in later years, when he lost interest in family/friends’ doings; I would never be scolded, criticized for going alone, but I would ‘catch hell’ when I did show up at home. I was never forbidden from going. I think it was his way of making sure I behaved, and what would be expected, if I didnt.