By Eleanor Cowan

By Eleanor Cowan

One bitterly cold winter’s morning at the Vendome metro in Montreal, I hopped a bus that would take me to a lecture on “Attentiveness and Developing Awareness” — and got a complete lesson well before I arrived at the class.

The driver of the vehicle, an unsmiling muscled-bound individual, closely examined my transfer for the minute expiry hour stamped upon it. With a curt nod, I was permitted to take my seat. About two minutes later, the driver revved up the ignition for departure, but not before an elderly lady rapped on the glass door, asking for entry. The driver looked down at her, examined his watch for the ten seconds it would have taken to open the door and admit her, adjusted the shift sticks and noisily tore off without her. I saw the aged woman bow her head and quickly step back onto the snowy sidewalk shelter as the bus swept away without her.

Shame flooded me. I could have done something. A fully functioning adult, I could have stood up and insisted the driver open the damn door – but I didn’t. Suddenly afraid, I froze. I squirmed in my seat. My hands began to sweat. My stomach clenched. Without warning, in that single moment, I’d regressed to a mute adolescent terrified of someone’s hostility and anger. I’d spiraled backward. Unexplainably, I even said a polite “thank you” to the jerk when I got off the bus to attend a lecture on a topic I’d just learned so much about.

That day, I did not hold the bar high for a frail senior who deserved so much better than the hostility she got – antagonism that my silence allowed. During the lengthy lecture and question period at the class, I found myself imagining different scenarios in which I played a heroic role. There I was, standing up, politely asking the driver to open the door and, when refused, insisting that the right thing happen on a cold winter’s day! I imagined three other more emphatic and colorful scenes – that didn’t happen. Wringing my hands during the lecture, I realized that I hadn’t acted according to my values. I felt disappointed in myself even after years of using my recovery tools. What had happened? I called a friend.

That evening, at the end of her shift, Jennifer, a critical care nurse, and I met for supper at her hospital cafeteria. My good friend listened as I shared my distress that I’d recoiled so suddenly on the bus that morning, that I’d just flipped into an impotent, fearful freeze.

“Look, Eleanor,” said Jenn, “let’s not diminish the accomplishment you’ve had in the past few years. Anyone on a recovery path is, without question, going to stumble. Count on it! It’s going to be up and down, up and down. It’s always 2 out of 3. The third will be the mistake, the screw-up, the blunder you’ll wish hadn’t happened. That’s where the word ‘apology’ comes in. That’s where we dust off the words, ‘Try again.’”

“I still see myself sitting there, utterly silent while the driver ignored the older lady’s request!” I said. “The poor older woman was rejected so rudely.”

“Perfectionism,” advised Jennifer, “is now classified as a shame-based mental illness in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Medical Disorders. Don’t even try to go there! What you are seeing today,” she continued, “is that the roots of early distress still lurk within, and, like the streptococcus bacteria strain, will never entirely disappear. Find some helpful ways to prevent flare-ups.”

Finally falling off to sleep that night, I decided that I needed to practice a kind of vigilance – a gentle watchfulness – and be kind to myself when I fell short. I valued the humanness in the “2 out of 3” idea Jenn had shared.

I decided to honor my fragility rather than attempt to erase it. I purposefully choose to volunteer inside strong teams where discussion and consensus happen. I find that the practice of consulting with others has strengthened me in ways I can take onto the bus.

When I think of that dear gray-haired woman today, I thank her. I whisper to her that she did not miss that trip in vain and that as a result, I’m on a better route. I’ve become an activist. Just the memory of her bowing her head in the snow motivates me to better deal with the “speak up” opportunities that come my way.

A city dweller, I sold my car years ago and love taking the bus and metro. This driver was one of the very few 1% I’d ever seen offend a passenger. Most are pleasant, welcoming and helpful.

While it was delayed, I stood in my sturdy winter boots at the Vendome station shelter the following day and luckily, got the requisite badge number of the rude chauffeur. I wrote a detailed account for the MTC, who called me the following week to say the driver got a stern warning which had been filed.

It was a late response, but better than none. In my forever evolution, I’m doing my imperfect best.

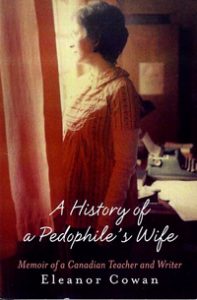

Eleanor Cowan is author of “A History of a Pedophile’s Wife,” which is available on Amazon.com. Visit her at eleanorcowan.ca

5 stages of endurance to help you recover from the sociopath

5 stages of endurance to help you recover from the sociopath

regretfullymine

you learn, by experience, which means making mistakes. and by making new mistakes, which adds more experience. im doing this. (aint easy, but keep going forward).