By Eleanor Cowan

By Eleanor Cowan

In my large family, so many of us were affected by our mother’s personality disorder that over time, our odd behaviors and adaptations became normalized. When neighbors asked about my mother’s terrible shrieking and screaming or her calling her children names such as “stupid brainless idiots,” I’d quickly minimize the damage and offer inauthentic responses. “Oh, our house is so big. She’s just calling everyone for supper.”

When I read, years later, that people swear according to their insecurities, I sensed my mother felt insecure about the education she lacked. Always guilt-free herself, she loudly blamed her older children for our toddler brother’s dangerous habit of stuffing tiny pebbles up his nose and deep into his ears, behavior that raised eyebrows at the local hospital emergency room. We said we were sorry for not having watched over him better. Even though my parents lost two infants to crib death, they remained unmotivated to protect my little brother. That was our job. The oft-repeated words, “I’m sorry, Mum,” became my mantra.

My relentless apologies planted in me a sense of guilt about events and behaviors over which I had no control. Slowly, over time, my personality warped.

When I confided my anger to my Dad, a salesman absent for most of my childhood, he found excuses for my overburdened mother — just before he left again. He’d remind me that, as Roman Catholics, anger is a sin and forgiveness a virtue. My father suggested I go to Confession, where I found myself admitting guilt, apologizing and resolving to become a better person.

By internalizing blame, I converted it to guilt, which in turn pretzelled into a bizarre sense of responsibility for people, places, and things. Somehow, I began to do chronic damage control, even at my own expense. If a family member was as rude to me as my mother had once been, I tolerated it because of our shared history. If a boss asked me to work overtime four weekends in a row, I did so, because, in addition to feeling exhausted, I also felt valued and appreciated. I worked very hard for the approval of others. Because I couldn’t seem to care about or stand up for myself, I was entirely dependent upon pats on the head from users.

Years later, my inability to honor my own life, and the lives of my children, resulted in my full membership in a support group for Parents of Sexually Abused Children. During one meeting time, when all of us sought to wake up to our participation, however unwittingly, in the stark and horrible fact that we were parents of abused children, we discussed the disassociation and grooming that brought us to this group. I said that over the years, I’d allowed the self-respect bar to descend. I talked about my chronic apologizing.

Suddenly, the lead Social Worker, Aidan, grabbed a dry erase pen and wrote out a script on the whiteboard. “This is for all of you,” she said. “If someone says they feel sick, do not say, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry.’”

Instead, she began to list alternatives such as, “Oh! I hope you feel better soon!” Or, “How are you taking care of yourself?” Or, “Is there anything I can do for you?”

“There are deceptive tactics used by all manner of unsavory characters to suggest your ineptitude, and to reduce your sense of self-worth,” said Aidan. “It’s called ‘priming the pump.’ Always stand up for yourself. Trust your gut. And cut the ‘I’m so sorry’ lingo, unless you did something you honestly regret. Don’t make it your business to sweeten or smooth over or placate, because by doing so, you play into a no-win game, one that says you’re always in the wrong and now need to compensate.

“Stop that nonsense,” said Aidan. “Time to get real!”

Life never stops being complicated and confusing. About five years ago, during a rare visit with a brother, he blurted out that he understands how people could hate me! I had no idea what caused this outburst. I haven’t seen him since. If my sibling would ever like to apologize, I’d be glad to accept that, but he hasn’t. There’s no longer any suffering on my part. It’s not always that way, though.

For years, I tolerated the harshness of another unpredictable relative, because of my wonderful relationship with his children. I so want to be there for them, but his last cruel salvo, out of nowhere, warned me to protect myself.

“I feel gutted,” I confided to a dear friend. “Must I tolerate abuse in order to love? Am I back to that?”

Along with keeping the bar high, there’s loss, sadness, and doubt.

Today, I trust that if I do the right thing, the right thing will happen. I’ve decided.

I’ll never again undervalue my life.

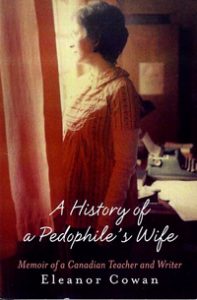

Eleanor Cowan is author of “A History of a Pedophile’s Wife,” which is available on Amazon.com. Visit her at eleanorcowan.com.

12 ways sociopaths say, ‘It’s not my fault’ — what have you heard?

12 ways sociopaths say, ‘It’s not my fault’ — what have you heard?