-

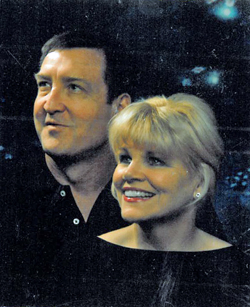

Kathleen Mills is president and CEO of the National Military Spouse Advocacy Organization. “Military spouses are at immense risk of being legally abandoned by their spouses,” she says. Chief Warrant Officer Herbert ‘Roger’ Mills wiped out the family’s accounts, filed for divorce and volunteered for Iraq at age 57

- Kathy Mills, a former teacher and Mary Kay director who won eight pink Cadillacs as a ‘Grand Achiever,’ was left destitute

- CW Mills took advantage of a law passed to protect service members so he could avoid divorce court

- CW Mills cut his wife out of his $500,000 military death benefits before parachuting to his death

- CW Mills wrote on the Ohio National Guard office white board that he would be in the hospital BEFORE he jumped

- Kathy Mills found her husband’s home and storage units filled with stolen military equipment and classified documents

- Kathy Mills wanted her husband investigated, but the Ohio legislature and Ohio National Guard honored him instead

BY DONNA ANDERSEN FOR DAILY MAIL ONLINE

An abridged version of this story was published by the Daily Mail on April 1, 2006.

For 10 years, Kathy Mills, a former special education teacher and Mary Kay sales director, has been at war.

Kathy, of Pickerington, Ohio, has been fighting her husband a West Point graduate and Special Forces operative, the Ohio National Guard and the United States Army. She wants the $500,000 she should have been paid when her husband abandoned her to deploy to Iraq and later died in a parachuting accident.

The response from the military, courts and elected officials? Mostly, 10 years of runaround.

‘The worst part was not being abandoned by my husband,’ Kathy said. ‘It was being abandoned by the military and abandoned by the court system.’

‘I had been a taxpayer, a contributing member of society. I believe character counts. But I had a scarlet letter put on me by the court. I was a bad Army wife.’

When Kathy married Herbert ‘Roger’ Mills at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, on Jan. 27, 1986, she thought she was marrying her best friend.

She’d met him when she was in high school. ‘We were close buddies. We hung out. We could talk about anything.’

But they’d gone their separate ways, married other people, and divorced. Mills was working for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company after his five years in the Army was up, and Kathy was teaching in Germany.

They reconnected. Suddenly Mills asked Kathy to fly to New York, drive to West Point, and marry him.

‘I thought it was so romantic,’ Kathy said. She said yes.

Years later, Kathy learned why Mills suddenly wanted to marry her: The only way he could keep his job at Goodyear was to have a wife.

It didn’t take long for the marriage to become strained. Kathy’s friends thought her larger-than-life husband was amazing he was 6-foot-5, 270 pounds, and an officer in the Army Reserve, frequently deploying to far-off places.

But Kathy had discovered his obsession with pornography, which upset her tremendously.

She endured his silent treatment. ‘At one point we lived in the same home, and he didn’t speak to me for three months,’ she said.

Money with Roger Mills was a nightmare. He lost the Goodyear job, and every job after that. ‘There was never going to be money with Roger,’ Kathy said, ‘always debt.’

So Kathy compensated she created her own life. She raised her two children from her first marriage. She worked full-time as a special education teacher. Through her Mary Kay business, she made an extra $100,000 a year and won 15 cars, including eight pink Cadillacs, as a ‘Grand Achiever.’

But Kathy was ashamed. ‘I don’t know why I am married to this amazing man, and everything is my fault,’ she said. ‘I can’t make enough money to keep plugging the holes.’

‘I can’t describe how weird it was,’ she continued. ‘He decides he’s in a funk. Okay, he’s in a funk. And then there would be moments of great family togetherness. It was all a big ball of confusion and unpredictability.’

After a frightening threat of domestic violence, Kathy filed for legal separation in 2001. Mills deployed to Kosovo and then wrote he wanted to work on their marriage.

So they went to counseling. Mills took Zoloft for his moodiness and testosterone for sexual dysfunction. After three cautious years, Kathy believed they had reconciled.

Now, she realizes, ‘he was a snake waiting for the right opportunity.’

In 2005, Mills launched his plan.

After losing yet another civilian job in Conneaut, Ohio, Mills was working for the Ohio National Guard.

Mills had always been involved in the military. After five years in Special Forces, he was a major in the Army Reserve, but never completed required courses for promotion. He retired from the Reserve and joined the Guard as an enlisted man a chief warrant officer (CW).

Kathy, believing her marriage was finally on firm footing, had given up her tenured teaching job in Akron, and her established Mary Kay network, to join her husband in Conneaut. When he was fired, they had two homes and massive credit card debt, so they couldn’t meet their expenses. Mills urged Kathy to liquidate her $126,000 teacher pension to pay off their debts. She did.

The Special Forces Group of the Ohio National Guard was called up to deploy to Iraq. Even though CW Mills had spent more than 30 years in the military, he’d never been in combat. So at the age of 57, he volunteered to go to Iraq.

He didn’t tell his wife.

In August 2005, CW Mills wiped out all their bank accounts. He filed for divorce in Ashtabula County, Ohio, and obtained a restraining order, preventing both he and his wife from selling or changing their assets, according to court documents.

Kathy had no full-time job, severely reduced Mary Kay income and no retirement fund. She had two mortgages and legal guardianship of her nine-year-old grandson. She retained a lawyer and filed for temporary spousal support.

CW Mills manipulated multiple military programs and regulations, and the gap between federal and state law, to deprive Kathy of any money, she said.

First CW Mills invoked the Service Members Civil Relief Act (SCRA). The SCRA provides certain protections for members of the military when they are called to active duty, according to Military.com. The law enables them to postpone civil court proceedings and judgments.

CW Mills kept arranging out-of-state temporary duty assignments, and kept invoking the SCRA to skip divorce court, Kathy said.

All branches of the United States military require service members to support their families. Army Regulation 608-99 states, “A soldier is required to provide financial support to family members.” If soldiers don’t, their commanders are obligated to intervene.

In fact, the Army pays solders to take care of their dependents. As a married soldier, CW Mills was entitled to extra money to cover his family’s housing expenses, called Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH).

CW Mills began collecting BAH payments at the “with dependents” rate on Sept. 1, 2005. According to Army regulations, in the absence of a court order, CW Mills should have paid Kathy $769.80 per month half of the BAH money he received. He paid her nothing.

CW Mills also collected $250 per month as a “Family Separation Allowance.” This money is supposed to provide compensation for added expenses incurred because soldiers are away from their families. CW Mills wasn’t eligible for the money because he had filed for divorce, but he collected it anyway. He paid his wife nothing.

In November 2005, Kathy notified her husband’s commanders that CW Mills was not supporting her. At this point, Army regulations required them to get involved.

Then at Thanksgiving, Kathy found out that her husband was deploying to Iraq in January. She was shocked.

Kathy went to Col. Deborah Ashenhurst, brigade commander of the Ohio National Guard. Nothing was ready, she told the colonel, crying. Her husband wasn’t supporting her, and didn’t sign her up for medical coverage. CW Mills couldn’t deploy.

‘Col. Ashenhurst said to me, ‘You don’t want to be a bad Army wife, do you?” Kathy related.

‘Through my tears I’m sitting at the table sobbing —I remember saying, ‘I don’t want to be a bad Army wife.”

Then on Dec. 7, 2005, without a hearing, Ashtabula County Judge Alfred W. Mackey signed an order temporarily denying Kathy any spousal support. A month later he overruled himself, saying that the court could not determine a specific support amount.

It shouldn’t have mattered in the absence of a court order, Army regulations clearly require soldiers to pay a portion of their BAH money to dependents, according to an analysis by Gene Brentley Tanner, an attorney the office of Mark E. Sullivan, author of ‘The Military Divorce Handbook.’

But commanders including Maj. Larry Henry, CW Mills’ immediate superior in the Ohio National Guard, Lt. Col. Robert Bramlish, director of the State Family Program, and Col. Kenneth E. Tovo, of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force – Arabian Peninsula, took no action to enforce the soldier’s obligation to support his wife, Tanner wrote.

CW Mills shipped out to Iraq, on what was supposed to be a yearlong tour. But the soldier’s performance record was always spotty.

‘He was capable of extraordinary feats of staff work and coordination,’ one commander wrote. ‘These laudable accomplishments were always riddled with unprofessional acts that often defied any rational explanation.’

During a Special Forces deployment to Kuwait in 2002, the commander stated, CW Mills’ behavior became so belligerent during a meeting of the entire company that the commander had to order him to the position of ‘at ease.’

In Oman in 2005, the commander stated, CW Mills would ‘scream using expletives and accusations that were beyond either my Company Sergeant Major’s or my understanding.’ The commander was forced to escort CW Mills out of the headquarters building, with another soldier as a formal witness.

So less than three months into CW Mills’ yearlong deployment in Iraq, Kathy said she received a phone call from a Special Forces attorney they were sending her husband back to the U.S., he’d been threatening to kill her, and she needed to protect herself.

On April 10, 2006, Kathy went to court for a civil order of protection her husband was to have no contact with her. He also had to give up all firearms. Police confiscated nine rifles and six pistols from the Mills’ home in Conneaut, Ohio.

Along with the order of protection, Judge Carol J. Dezso, of Summit County, Ohio, awarded Kathy $1,800 a month is spousal support.

Kathy never received it.

Kathy continued to contact her husband’s commanders and other military officials about his lack of support. CW Mills continued to fight her in court.

If her husband wasn’t going to pay her the BAH money that he collected as a married soldier, Kathy said, then she wanted him prosecuted for defrauding the United States government.

She sought assistance from Ohio Governor Ted Strickland, as commander in chief of the Ohio National Guard. She also asked Senator Sherrod Brown, and Congressmen Steve LaTourette and Ralph Regula, for help.

Kathy even filed a “complaint for writ of mandamus,” which is a demand for government officials to properly fulfill their duties. The complaint named Gov. Strickland, other state officials, Lt. Col. Robert Bramlish, Brig. Gen. Matthew Kambic and Brig. Gen. Jack Lee.

Nothing happened. The divorce battle wore on for five years.

In the meantime, commanders at the Ohio National Guard grew tired of CW Mills’ insubordination. Lt. Col. Paul. D. McAllister wrote a personnel memo on March 5, 2009, documenting that ‘CW Mills is unable to work with traditional commanders and others in a professional manner.’

Lt. Col. McAllister limited CW Mills to a desk job at Ohio Army National Guard headquarters in Columbus until his mandatory retirement date.

Yet on Wednesday, Oct. 20, 2010, CW Mills was the jumpmaster for a parachute training jump at Rickenbacker Air National Guard Base in Columbus, Ohio, even though he no longer qualified for the responsibility.

CW Mills landed hard on concrete, cracked his helmet, jaw and the back of his skull, and was dragged by his parachute into a ditch. His fellow jumpers did not look for him immediately because CW Mills was known for not reporting to the assembly area, according to the official investigation. He bled for almost an hour before he was found.

Four days later CW Mills died of his injuries. The investigation attributed his death to ”˜jumper error.’

But after the accident, Kathy learned that a female sergeant who worked with CW Mills saw him write his upcoming schedule on the office whiteboard: ‘Wednesday jump. Thursday hospital. Friday hospital.’

Kathy believes her husband planned to be injured in the jump. She had finally won her battle for support, and the court in Summit County, Ohio, was garnishing $1,600 per month from his Ohio National Guard pay.

‘He had to jump, then walk away with a back injury, which is hard to diagnose,’ Kathy explained. ‘He’d go to a physician’s assistant and get diagnosed with 100% disability.’

If CW Mills received Veterans Administration disability payments, which are tax-free, Kathy could not claim the money. VA disability payments cannot be divided as marital or community property in divorce, according to federal law.

When Kathy went to her husband’s home and two storage units after his death, she found that they were filled with stolen military equipment guns, ammunition, lockers, C-rations and even award plaques, engraved with men’s names.

She also found DVDs stamped ‘classified,’ and numerous personnel files including files on generals. She called the military. Five soldiers came to remove the materials, filling two SUVs.

Kathy wanted her husband investigated.

Instead, a year after his death, Ohio Senator Frank LaRose sponsored legislation naming the parachute drop zone at the Rickenbacker Air National Guard Base in his honor. The Ohio National Guard Special Forces soldiers held a parachute jump and ceremony to commemorate CW Mills. Kathy was not invited.

When CW Mills died, their divorce was still not finalized, so Kathy was his widow. She believed she would receive his $400,000 Service Members Group Life Insurance (SGLI) payment, and the military’s $100,000 death gratuity.

Kathy was wrong.

A year earlier, CW Mills had removed her as the beneficiary for both payments, despite the civil restraining order in their divorce that CW Mills, himself, had implemented.

Kathy said that his commander, Maj. Jeff Watkins, signed the change of beneficiary form and placed it in CW Mills’ file. She said this did not follow Army procedures. The form should have been processed by the unit’s personnel department and uploaded to the personnel database.

The $400,000 went to his brother tax-free. And $75,000 of the death gratuity went to Mills’ brother, sister and mother.

The soldier left behind marital debt and unpaid taxes. ”˜The IRS came after me,’ Kathy said. ”˜I was the one that bore the burden of the $60,000 tax bill, with no insurance.’

Kathy was never notified by the military of her husband’s beneficiary changes.

Members of the military can choose anyone they want to receive their insurance money if they die. SGLI policy requires spouses to be notified if soldiers change coverage.

But this regulation has no teeth, because SGLI policy also specifically states that if the Department of Defense fails to notify the spouse, nothing happens. The spouse has no recourse.

Whomever the soldier named gets the money, even if the spouse had no idea of any change or cancellation of coverage, and even if the spouse and children are destitute.

The Ohio National Guard chose not to investigate why Kathy was never notified that her husband removed her as his insurance beneficiary.

Kathy was able to get some money from the death gratuity. She received $40,000 of the standard $100,000 payment, because the military acknowledged errors in how CW Mills filled out the beneficiary form.

But Kathy contends she should have received the entire $100,000 death gratuity, and the $400,000 insurance payment, because her husband violated the restraining order in their divorce, and the U.S. Army violated its own policies and the law.

The Army twice denied her claim. Kathy is now appealing.

Through her ordeal, Kathy has become an expert on military regulations and policies on family support. So she’s been helping others who have been abandoned by their military spouses.

In 2006, Kathy became the divorce editor for a website for military families, which is now defunct. She has helped more than 1,000 wives abandoned by their military husbands along with two husbands abandoned by military wives.

‘We don’t know how big the problem is,’ Kathy said. ‘There is no tracking in the Department of Defense.’

It’s big enough, however, that the Defense Department has posted an article called ‘Rights and benefits for abandoned military spouses’ on the MilitaryOneSource.mil website.

”˜The article was written to let abandoned military spouses know that they have certain rights and benefits to help them through this challenging process,’ says Maj. Benjamin E. Sakrisson, Defense Department spokesman. ”˜Knowing rights and benefits can help protect them and their families.’

EX-POSE is a non-profit organization that helps military spouses in the divorce process. Office Manager Nancy Davis says she gets a call nearly every week from a military spouse who has been deserted or abandoned by a service member.

In a typical abandonment case, Davis says, a military spouse calls and says the service member left days, weeks or months earlier, and she has no money for food or shelter.

”˜There’s a huge BAH fraud problem,’ Davis says. ”˜I don’t know that the military has done anything to address it.’

Kathy Mills is now president of the National Military Spouse Advocacy Organization (NMSAO), which she and other abandoned military wives founded last year.

”˜The NMSAO has initiated a campaign to stop service member abuse of financial allocations and close legal loopholes that allow military service members to financially abandon their dependent family members,’ Kathy says.

Changes proposed by the NMSAO include allowing military spouses to purchase separate life insurance policies on the service members, distributing death gratuities to spouses when they have not been notified of beneficiary changes, enabling separated spouses to directly petition the military for half of a soldier’s BAH pay.

‘When men are in uniform, all of society wants to believe the soldier is good,’ Kathy said. ‘We all do. I still do.’

‘My son is in the military, and I believe he is good. I want to believe the man next to him is good. But they’re not all good.’

Kathy is still helping abandoned spouses who find her on the Internet and Facebook.

‘When you’ve gone through the pain, and you know what the person on the other end of the phone line is feeling she can’t breathe, she’s crying all night, she’s alone. The moment I can interject myself into her world, she is lifted. She is not alone,’ Kathy said.

‘This happened to me. I can walk away from it. But if I choose to look the other way, I’m not living in a value, I’m not living in a purpose.’

‘These women have served they’ve raised the next generation of soldiers and officers,’ Kathy said. ‘It’s important to have a good army. It takes families to do that.’

Count the psychopaths in ‘Hell on Wheels’

Count the psychopaths in ‘Hell on Wheels’