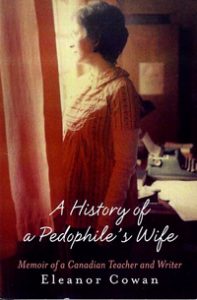

By Eleanor Cowan

By Eleanor Cowan

I was eleven years old. “Do you know what you are? asked Mother, thrusting open my bedroom door to find me, as she knew she would, in a predictable spot reading a predictable book. “I’ll tell you who. You’re a big, fat, lazy nothing.” Waving her souvenir from Mexico, a horsewhip, she flicked my hair up at the back as I hit the stairs to begin new tasks.

Even though I weighed less than a hundred pounds, even though my chores were done and I’d earned the right to read for awhile, I did not defend myself. There was no talking back, no disrespect, no arguing. Only one rehearsed sentence was permitted. I said it: “Yes, mother? What can I do to help?”

Standing up for myself would have meant facing both my father, a traveling salesman on the road half of each year and then, at Confession, Father Rich, the man who believed my mother was a shining example of religious womanhood. The priests lived far enough away that, unlike the neighbours, they remained ignorant of Mother’s constant screaming, yelling that ceased when visitors appeared. Still, I sought my mother. I needed her affection. I spared no effort to earn her approval. I tried harder to please her. While I cannot recall ever receiving a hug or a kiss from her, I do recall a few smiles from her serious face – but these were not directed at me.

For some odd reason, my mother’s insults drove me on. I’d show her! I’d clearly demonstrate that I wasn’t a “colossal idiot, a dumb bunny or worse, a lying tart.” She’d be proud of me one day.

I had no idea that eighteen years of “name-calling” had any effect at all – nor that it was abuse. I never stopped doing my best to convince my mother that I was worthy of her love. Even more confusing, her rare moments of thoughtfulness somehow erased months of cold hurtfulness. My solution was to assume responsibility. I’d gotten it wrong. I’d try to be a better person. I took full responsibility. I began to beat myself up for minor mistakes. In this way, I assumed full control and all blame. I apologized a lot.

It took me decades to realize that the two adolescent boys my parents adopted were, in fact, used as servants in our home, as were the five older children who became parents of our five younger siblings as soon as they arrived from the hospital.

I was pleased to see that one afternoon, mother invited Mrs. Rio, a widow with three little boys, over for a visit. Soon after, however, the struggling mother found herself with four children to care for, my baby sister added to her responsibilities while Mother left for holiday. This was the beginning of mother’s giving her children away, one by one, to whoever would take us on.

When she applied for and won a Best Mother Award in our county, one that came with a washer, dryer and some cash, I wondered why I felt so upset. I had no vocabulary for the dark distress roiling inside. During her public celebration, I stole sugary Rocky Road ice-cream from the freezer and ate it all by myself in the basement. Mother then dubbed me “the ice-cream thief.”

I wish I could say that I had an aha moment where it all came together for me. After I left home and got a good paying job in the city, Mother called regularly, asking for money. She’d stay on the line with me to help me figure out my next payday, how much I could send, and the exact day she’d be at the post box, waiting for my check. She made me promise that I wouldn’t let her down – and not to discuss my gifts with my siblings.

Only much later, did my sisters and brothers share with me that they’d also contributed on a regular basis. When my mother ended her own life because her boyfriend decided he needed a better-quality mate, I was still living in a dark basement of unconsciousness, eating ice-cream, secretly binge drinking and always a) blaming myself and b) trying to be a better person – trying to qualify for love.

A year after my mother’s death, at 25, I married a pedophile, a man who assured me he’d greatly appreciate my love, talent and financial support for the amazing doctorate he’d soon earn.

Fourteen exhausting years later, at 40, with the help of our sexually-abused daughter, I arrived at the top step of a cobwebbed cellar door, and opened it.

At my first meeting at the Parents of Sexually Abused Children, our social worker warmly welcomed us with words of non-blame, “There are thousands upon thousands who’ll never, ever get here. I’m so glad, so proud and so grateful that you have”

I still remind myself to not be ashamed of how dissociated I was. I’m just grateful that I woke up to begin my authentic life.

Eleanor Cowan is author of “A History of a Pedophile’s Wife,” which is available on Amazon.com. Visit her at eleanorcowan.ca